No French Dancers!

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]

In Autumn 1754 David Garrick began the negotiations which would bring Jean-Georges Noverre’s ballet company from Paris to Drury Lane. Garrick was interested in Noverre’s innovative work; it might out-class Drury Lane’s incidental dances, but it would steal a march on Covent Garden. Noverre’s major work, Les Fêtes Chinoises, would draw a fashionable audience smitten with the craze for chinoiserie.

The lawyers on both sides pursued a Byzantine path, procuring the most artistic marvels on the least sum possible. Noverre protested that he was better paid at the Opéra Comique, though it would be ‘dark’ during the London season. Garrick must decide how much he could afford quickly, for Noverre had a lucrative offer from the Bavarian court.

Terms were agreed, Noverre made a recce to Drury Lane and the lawyers fell to negotiating over décor and personnel. Patu, Garrick’s negotiant, recollected in the course of finding enough female dancers ‘three little trollops’ whom he had seen dance in London. ‘Woman’, wrote Noverre to Garrick, ‘is an expensive if common merchandise’, Madame Noverre excepted: ‘I could not live in London without my wife. See if she could be of use in your pantomimes; she would dance in my ballets.’ He had summed up the differences between Garrick’s dancers and his own.

Of Noverre’s company of 60, 40 were British and a third of the rest were his family. Mme Noverre (née Marguerite Louise Sauvery) was ‘useful’. Her sister Nanette Sauvery was a principal dancer. Noverre’s reference to ‘my little sister’ may be to a Noverre or a Sauvery. ‘Miss Noverre’ was his six-year-old daughter, Claudine, who danced with a group of children. ‘A little girl to dance Cupid’ was younger still – this was normal at a time when Frederick Menage, aged three, danced Cupid at the Pantheon in 1791. Also in Noverre’s company was his younger brother, Augustin, b.30 April 1729. Noverre himself was contracted to dance ‘unless my accident should prevent my dancing’, and to be paid as ballet master. He had broken his Achilles tendon and did not, in fact, dance in or after 1755.

Garrick’s ambitions were overtaken by Franco-British hostilities which would lead to the Seven Years War. Ill-founded press reports of imminent invasion provoked Francophobia. But there was France, and there was Paris, and the fashionable, educated and bilingual Parisophiles wanted their treat. Garrick issued a defensive press statement: Noverre was a Swiss Protestant, his wife and her sisters were German. The company were anglicised to Mr, Mrs, Miss and Master. But they were from France, and so was the enemy.

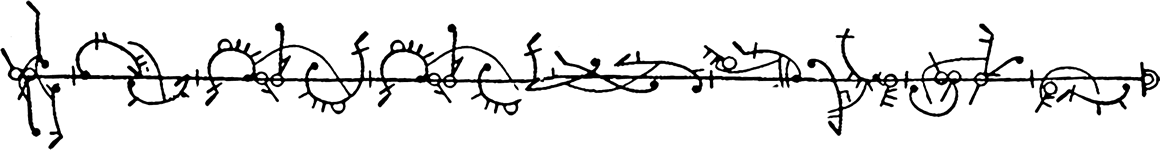

Noverre eased himself into the situation by presenting small incidental works: Miss Noverre and Young Pietro in La Provençal, a small group in ‘a NEW DANCE by Signor Baleti, Mr Lauchery, Mrs Vernon and Miss Noverre’. The children, led by Claudine and Young Pietro, danced The Lilliputian Sailors. So far, so well received, but the major work eclipsed Garrick’s own dancers, a mediocre corps de ballet’ as Noverre saw them, and provoked riots.

The King chose for a Command performance on 8 November 1755 The Fair Quaker of Deal and the premiere of Les Fêtes Chinoises. Royal presence restrained the audience but there were shouts of ‘No French dancers!’ from the gallery.

Fêtes was next presented to an audience previously sweetened with Much Ado about Nothing. The fourth performance coincided with an opera night; the Nobility decamped to their boxes at the King’s Theatre, and Drury Lane was held by the Francophobes whose threats kept the dancers in the wings.

On 18 November, following the tragedy The Earl of Essex, Fêtes was abandoned on ‘the great destruction of Mr Garrick’s plans and property’ (Charles Burney). The auditorium and scenery were wrecked. In the armed melée on stage, in which performers tried to separate parties for and against ‘French ballet’ Augustin Noverre ran a man through. The victim would recover but, for the moment, reprisals were feared.

Garrick patched up his theatre and his house to which fighting had spread. More immediately the Noverres were hastily hidden. Accounts of what happened vary. Lynham and MacIntyre repeat

C E Noverre’s version: Augustin went into hiding in Norwich where Huguenot weavers provided sympathetic French-speaking cover. Lynham adds: ‘The whole family went into hiding’. The fate of non-family company members is not mentioned. Chéruzel’s version is: ‘La famille, démunie, se cache à Norwich avec Augustin et son épouse.’ Augustin had married within the year and his bride fled with him.

Hm… Hiding six people is very clever. Isn’t a bit of the story missing? Why Norwich?

Perhaps one of Garrick’s company had played in Norwich and knew of useful cover and a safe address. It may have been Garrick who knew; his father’s family came from Bordeaux and he himself was bilingual. First Augustin, then the rest of the family, were bundled into coaches and sent to safety – out of the way of further damage.

Chéruzel says that Jean-Georges decided that Augustin should stay in England where he now had friends – possibly inferring an English bride – while the rest of the family returned to France. In effect Jean-Georges ejected Augustin from his ballet company. Of the ‘épouse’ there is no further mention or trace.

Jean-Georges may have returned to London very soon to gather up his company and present small works. Fêtes could not be presented again; the scenery was wrecked. Noverre had not yet returned to Paris by 13 February 1756; Patu wrote to Garrick on that date to ask when he might expect Noverre’s return. The Noverres were, in fact, making amiable visits to the Garricks at Hampton. The wives were both dancers. The husbands praised each other as ‘the Anacreon of England’ and ‘the Shakespeare of the Dance’ – or more mischievously ‘that most fantastic Toe’. They shared an ambition to prune the stage of excessive artifice.

In spite of the riot that he had provoked, Jean-Georges asked if he might return for the 1756/57 season. And in spite of Garrick and his financial manager, Lacy, advising against the proposal a smaller Noverre company returned for a less eventful season. Jean-Georges could be bone-headed in his pursuit of career and ideals. In this season and in the future he broke his contract when better fortune beckoned elsewhere. He asked Lacy for permission to leave in March 1757. Lacy did not pay him for work not performed. Madame Noverre wrote to Garrick with a sharp pen: they remained the Garricks’ most cordial friends, but Mr Lacy did not sufficiently value M. Noverre.

Meanwhile, at Lyons Opéra Jean-Georges created his first ballets d’action, not frivolous divertissements but dance integral to the opera it accompanied, performed in rational costumes, not in stage versions of court dress, and without masks. He published his theories in 1760 as Lettres sur la Danse et sur les Ballets, dedicated to the Duke of Wurtemburg who invited him to Stuttgart with generous financial inducements. There was no comparable patronage in London.

Jean-Georges was not the sole inventor of ballets d’action. John Weaver had explored similar ideas at an earlier date in England, but Jean-Georges was the practitioner of his generation who formulated naturalism in dance.

In 1767 he offered his services to Garrick ‘if Lacy is not opposed’, but he did not in fact return to Drury Lane in 1767 or in the future. His career lay in the opera house.

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]