Jean-Georges at the King’s Theatre in the 1780s

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]

In 1781 Jean-Georges was forced to ‘retire’ from the Paris Opéra but secured from the management an annuity. The Opéra burned down in June 1781 and the company relocated. He was now free to spend a season at the King’s Theatre in London and he lived at 40 Great Marlborough Street, which might indicate that Augustin had moved to no.48 by this date. The brothers must have met often, but their private lives were exactly that; we know more about their professional than their personal lives. They cannot always have figured as the grumpy elder brother and the blundering sibling.

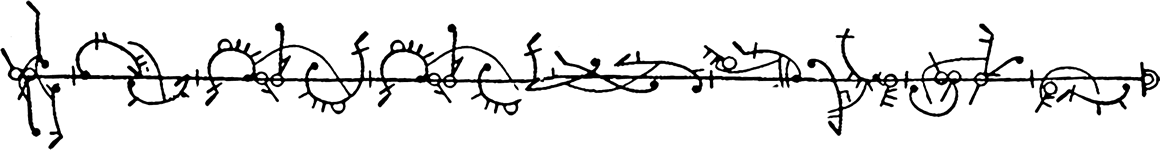

Jean-Georges brought with him a mainly French company which caused no xenophobic outrage at the King’s, but his serious and tragic ballets disconcerted those who expected ballet to be a frivolous diversion. His ideal was that ballet should be an independent art and not the common embellishment of opera: divertissements at the end of each act and a more substantial piece as a finale. Worse still, opera house managements hitched inappropriate ballets to opera, which is why Mozart wrote his own ballet music for Idomeneo.

Mozart and Jean-Georges worked together to try to integrate opera and ballet, but they also failed to live up to their own ideals. Mozart’s Les Petits Riens was intended as a ballet to accompany Alexandre et Roxanne. The score was planned with Jean-Georges, but the two works were never performed together. At the King’s in 1781/82 Jean-Georges dispensed with Mozart’s score and staged a new Petits Riens with music by Barthélemon, the King’s band leader. So much for consistency.

Alceste, a serious ballet paired with the tragic opera Giulio Bruto, was received by the boxes with rapture. Jean-Georges modestly refused to take a curtain call in deference to London custom. The critics, however, were not so enraptured; Bowkitt of the Morning Herald wrote: ‘Can anything be more ridiculous than to die dancing.’ Competitors mocked what they could not achieve; a burlesque version was performed at the Royal Circus.

Four more ballets d’action were performed, including Rinaldo and Armida with the final immolation scene; Adela of Ponthieu in which a duel with axes and broadswords required coaching from Mr Angelo, the best riding and fencing master in London. Medea and Jason was a rebuke to Vestris sen. who was Jason in Jean-Georges’ original production and who had presented a pirated version at the King’s in the previous season and so was first to present ballet d’action in London.

Jean-Georges did not neglect light entertainment. He devised dances and costumes for a Masquerade on 24 January 1782, commended by the Morning Chronicle: ‘… if Mr Noverre showed his skill in composing the dances he did not betray his taste in devising the dresses which were extremely well executed.’ The corps de ballet had already been praised for their ‘decent and uniform costumes’, then an unusual regularity. Attention to detail included a fully lit auditorium for a rehearsal ‘as for a performance’. Patrons demanded lighting during performance so that they could read their libretti – and study each other’s dress. The tin-man, who managed the lamps, was paid per thousand lamps. Principal dancers, unlike singers, demanded full lighting for their benefit nights. Ballet was an expensive art. Masquerades were always ‘brilliantly lit’, hence the attention to costume.

When the King’s went into administration in the following season less money was spent on ballet. The ballet masters, le Picq and Dauberval, were a poor replacement for Jean-Georges. The Morning Post found le Picq’s ballets ‘pantomimical … Lacking in grace and elegance’. His Macbeth, with Barthelémon’s music based on Scottish folk songs, pandered to the boxes, whose occupants had also seen Mrs Siddons as the Scottish Lady that year.

By 1787, ballet standards at the King’s had fallen to the equal of Drury Lane novelties: ‘a fandango by Miss de Camp and Master d’Egville.’ Children were cheaper. ‘Let us have un ballet d’action!’ begged The Morning Post.

In November 1787 Jean-Georges was persuaded to return although he protested that his health was poor and he was unable to compose dances for a masquerade. He presented Adela of Ponthieu – the duel filled the boxes and the coffers. On 29 January 1788 L’Amour et Psyche was such a success that it impressed the dance-unconverted Charles Burney: ‘The effect of this ballet was very extraordinary.’ Jean-Georges was carried on stage on the shoulders of his dancers to receive an ovation – and then criticised for offending London mores, although it was normal practice in Paris.

At the end of the season, Jean-Georges and his dancers borrowed from the Opéra returned to Paris. The dancers were subjected to mean-spirited reviews. Jean-Georges, looking for dancers for his next season at the King’s, was involved in a plot to oust Gardel sen. from the Opéra. D’Auvergne of the Opéra management described Jean-Georges as ‘grumpy … drunk as a cab-driver.’

Jean-Georges returned to the King’s for the 1788/89 season and lived, as usual, at 40 Great Marlborough Street. His ballet company was inferior because the King’s refused to afford better dancers. Once again he found himself the target of riots, not because he and his dancers were French, but because they were ‘wretched … like heavy cavalry.’ On 7 March 1789 ‘the ladies screamed and fainted … the gentlemen became riotous, trashed the scenery and broke every lamp in the house.’ The audience demanded that Jean-Georges answer for inferior entertainment. He replied:

‘Point d’argent, point de ballet. La troupe … n’est pas suffisante pour vous donner un spectacle très brillant … la faute n’est pas à moi.’

You may well ask: was there no opera in this opera house? Answer 1: Yes, especially in the boxes. Answer 2: Yes, but the manager, Gallini, and he an ex-dancer, did not skimp on opera productions.

This episode demonstrates that the audience had an informed interest in dance. And it was not new; Dr Johnson’s response to a night at the King’s in Vestris’ 1780/81 season is telling:

‘Sir, I went to the Opera. Yes sir, I went to the Opera to see Vestris dance. I like to see any man do anything that he does better than all the world beside.’

In 1789 Gallini was forced to make amends; he hired Mlle Guimard from the Paris Opéra for 650 guineas for the remainder of the season. Guimard, not in her first youth, was dubbed ‘the grandmother of the Graces’ and caricatured as Mlle Grimhard.

Jean-Georges presented Les Jalousies du Serail to a barely placated house. By 21 May, when the ballet was included in his benefit night, he had left the country, ceding his benefit rights to Gallini. He missed the finale of this melodrama; on 17 June the King’s Theatre burned down. (He seems to have quitted several posts leaving a slow fuse to act behind him.)

The company at the King’s relocated. Mlle Guimard was offered a smaller contract and less pay. She became litigious and was sacked. She returned to Paris and retirement. Jean-Georges would return to the re-built theatre in 1792 and his story will continue in due course.

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]