Augustin and Jean-Georges retire

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]

Augustin was 68 years old when he moved to Norwich to live with Francis in 1797. I think he had retired professionally, but it is hard to tell because of the private and unadvertised nature of his practice. He does not appear to have been in practice with either of his sons at any time. The era of Messrs Noverre, or Noverre and son, begins with Francis and Frank.

It may be significant that Augustin did not retire to Norwich until after Jean-Georges left London for the last time. The 1793/94 season at the King’s did not begin until January 1794. There is a gap of six months after the end of the previous season in which Jean-Georges was in England, probably chez Charles or even chez Augustin, but there is not a clue as to where he was and what he did at this time.

In 1794 at the King’s Jean-Georges had choreographic help from D’Egville and a mediocre company best suited to rustic nonsense such as L’Union des Bergères. A more adventurous Pigmalion ou la statue animée was ‘promised in a few days’ but never presented.

Lord Howe’s victory over the French fleet, the Glorious First of June, involved Jean-Georges in flag-waving on behalf of the country which held him prisoner. A celebratory programme given on 23 and 24 June and 1, 3, 5 July consisted of:

- La Serva Padrona. One-act opera by Paisiello in which the star was Mme Banti.

- A violin concerto in place of the usual second ballet, incorporating the melodies of Rule Britannia and Hearts of Oak.

- La Vittoria, cantata by Paisiello, adapted for the occasion, Mme Banti as the Goddess of Victory.

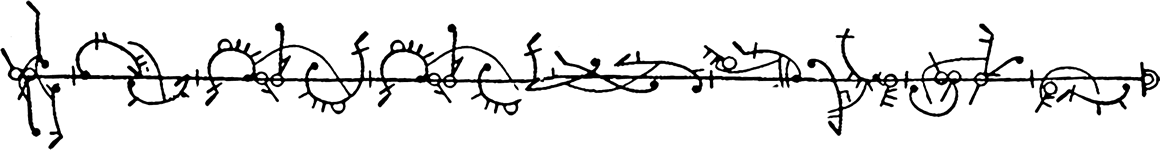

- Grand Allegorical Ballet by ‘Sir George Noverre’, including a hornpipe by Mlle del Caro – in travesty.

- Rule Britannia and God Save the King sung by Mme Banti.

The 1794 season was officially Jean-Georges’ last at the King’s but he remained interned in England. Onorati was ballet-master in 1795 but Jean-Georges choreographed ‘the pantomime and dances’ for an opera after-piece, Ati et Cibele by Cimarosa. It was performed on 14 May at the benefit night for Mme Morichelli, the opera buffa star – making a bid for the opera seria position held by her rival, Mme Banti. Ati et Cibele was an avant- garde work in which Jean-Georges achieved his wish to integrate opera and dance. The work was for one singer, Morichelli, as Cibele, and one dancer, Mlle del Caro in travesty as Ati.

The scenario lives up to the notion that opera succeeds by excess. Ati, the platonic beloved of Cibele, was put in charge of her temple on condition that he remained a virgin. He fell in love with a nymph and Cibele’s wrath drove him to insanity and self-castration. Violets grew from his spilt blood. The myth is a gift to a daring choreographer; the rites of Cibele include ecstatic dances, madness and self-mutilation. Ati is often represented with a a tambourine; Jean-Georges could at last dissociate the popular Tambourine Dance from the tarantella. He may also have tried to make a serious travesty role.

Travesty was what ballet had become at the King’s, mostly as an attempt to regain the attention of the audience from the rival opera divas. As well as del Caro’s Ati and her hornpipe there were the Hilligsberg sisters in a Pas Russe and a Scotch Reel, both performed in travesty. I don’t think Ati et Cibele was ever performed again, but it was a startling exit line for Jean-George.

He returned to France later in 1795. By late 1796 he was living in Paris near the Opéra, poor and in need of employment. The authorities who had requisitioned his savings were happy to praise ‘Citoyen Noverre whose talents are universally known and have been so valuable to the Théatre de la République’. In 1797 he was promised the post of Maître de Ballet at the Opéra ballet school and a 200-franc payment was authorised, but the Directorship of the Opéra changed hands and plans for the school stalled. Jean-Georges eventually recovered 600 of his lost 3000 francs after an exchange of ‘salut et fraternité’ letters with the authorities.

On 1 December 1798 Jean-Georges became Head of the School of Dance but apparently without much active participation in it. By 1803 he had retired with his wife to St Germain en Laye where they lived near another remarkable survivor of the revolution: Madame Campan, once secretary to Marie Antoinette, now mistress of a boarding school for girls of good Republican family.

Jean-Georges was invited to rehearsals of Medée, revived for Vestris junior’s benefit night on 12 April 1804, but after three rehearsals he made a grumpy exit and complained about poor standards and shabby treatment to the Opéra director. He could insist on high standards only with a pen in his hand, and he now revised and expanded Lettres sur les arts imitateurs published in 1807.

He died in St Germain en Laye on 19 October 1810. Elizabeth MacLachlan of Toronto, his great-great-grandniece, writes ruefully ‘… not only is J-G’s gravesite under the market place, but the house where he died has been replaced by the railroad station.’

Augustin enjoyed a comfortable retirement. His will, detailed below, gives us some idea of his material circumstances at The Chantry where he had Francis’ future in mind and his family a few steps away. There is little to tell us how he spent his last years aside from sitting to Joseph Clover for his portrait. It was painted before 1804 when Clover left Norwich to study with Opie in London. Perhaps Augustin graced Francis’ pupil balls like Mr Turveydrop senior while Francis played must-dash-now Prince Turveydrop.

Augustin died on 23 August 1805 aged 76. He was buried at St Stephen’s and his memorial is dedicated to ‘Augustin Noverre Gentl.’ His obituary in Bell’s Weekly Messenger in London 1 September, with almost identical versions in the Norwich Mercury and the Norfolk Chronicle must have been the work of Francis and Charles.

‘Augustin Noverre Esq … a native of Switzerland … . He was considered the most finished, elegant and gentlemanly minuet dancer that ever appeared. He quitted the stage nearly at the same time as [Garrick] for the private exercise of his profession as a Master, and by his simple and scientific method of instruction has done more to advance his art than any other man. He was esteemed by his pupils amongst whom were most of the Nobility of the Kingdom.’

Augustin’s nationality is fudged. He was born in Paris to a Swiss father and a French mother. Evidently his nationality at birth was decided by paternity. His father was an officer in the Swiss army. Father and son claimed the status of gentleman from their respective professions. The Norfolk obituaries make no reference to Augustin’s local teaching.

He made his last Will a fortnight before he died. It is a pragmatic Will: his executors were Francis and Louisa, who were near at hand. Charles was left objects of value: a gold watch, chain and seals; and three pictures, one of which was by the scenic artist Loutherbourg. This seems a curious way to treat one’s eldest son, unless Charles was already provided for. If Augustin had property holdings in London (such as the two Great Marlborough Street houses, one of which Charles lived in) they may have been made over to Charles at an earlier date.

Louisa received ‘my Irish Annuity wherein she is nominee’, household linen, wearing apparel, household goods and ‘pictures, paintings, prints and drawings’. Augustin seems to have had an interest in fine art but I don’t think it amounted to a lucrative sideline.

Francis was left the lease of the house in The Chantry, the appurtenances of the house, garden and stable, and the garden plants. No horse or carriage is mentioned; perhaps this was something to which Francis aspired.

Francis and Louisa were left equal shares of money remaining after the payment of debts and fees. If there was a deficit they were to bear it equally.

Augustin left the care of ‘my old and faithful servant, Elizabeth Stevens’ to his three children, ‘trusting that she shall not at any time during her life want a reasonable and proper maintenance.’

No manservant is mentioned. The will was proved on 26 February 1806.

Comparisons are inevitable. From the time their careers diverged in 1755, Jean-Georges and Augustin worked in separate spheres but shared certain aims. At Drury Lane Augustin worked in a gaudy, riotous and rackety world, nobility in the boxes and prostitutes parading in the foyer. At the King’s Theatre, which also staged plays, oratorios, concerts and masquerades, Jean-Georges found a gaudy, riotous elite, dissatisfied with second-best and with a capricious interest in singers and dancers – to the despair of musicians such as Charles Burney. Jean-Georges was at home in this world, Augustin was not, and he left it to make a good living at a smart address.

Both brothers sought patronage from high society because that was how their work prospered. Jean-Georges occasionally turned dancing master to please his patrons. He taught Marie Antoinette and her brother as children when his patroness was their mother Empress Maria Theresa. In the same period, on 16 February 1774, Sir Robert Keith, British ambassador in Vienna, wrote to his sister:

‘… sixteen couple of our chosen belles and beaux put themselves under the direction of the great Noverre in order to learn from him one of the prettiest figure dances.’

But such commissions were an occasional diversion from Jean-Georges’ real concern: his ambitions for ballet and his ballet students.

Jean-Georges never achieved in England the patronage which he won on the Continent. He may have hoped for royal patronage with his flag-waving ballets of 1793/4, but it was his dancers who went to court. In 1791/2 Pierre Gardel received a royal command to give dancing lessons to the Prince of Wales. He also arranged dances for a ball given by Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire. In the previous season Vestris senior gave dancing lessons to the Duchess. They devised the Devonshire Minuet, which Vestris tweaked a bit and inserted in the ballroom scene of Ninette à la Cour. The Duchess attended the ballet but left immediately after ‘her’ dance to the disgruntlement of the audience who had come to watch the notoriously spendthrift Duchess.

Augustin achieved the patronage of the Earl of Lindsay, to whose daughter he dedicated a minuet. Francis achieved by a kind of accident the patronage of the Earl of Craven, but that was for his extra-curricular activities.

Augustin remains a fugitive figure. We have his portraits and one of his dance collections, but ‘Goddem’ aside, we do not hear him speak. A piece of him remains in a mourning brooch, given to Norwich Museums in 1908 and described thus:

‘… oval mourning brooch, central part of woven fair hair surrounded by seed pearls; gold convex back engraved Augustin Noverre d. Aug 25th 1805 aged 76.’

In Clover’s portrait Augustin wears his own hair, fair not grey. His date of death is recorded as 23 August elsewhere.

Augustin probably applied his exasperated ‘Goddem’ to recalcitrant pupils but he does not seem to have shared his brother’s bad temper. Jean-Georges’ backstage behaviour was recalled in the Reminiscences of Michael Kelly, a singer and co-manager at the King’s in 1793. At a performance of Iphégénie en Aulide, Kelly, masked, was in the wings waiting to take part in a procession for which horses had been hired from Astley’s to draw a chariot. Astley’s supplied the ostlers, but they were drunk. Kelly took charge of the horses and restrained them too loudly. Also in the wings was Jean-Georges:

‘But he was a passionate little fellow, he swore and tore behind the scenes … he might really have been taken for a lunatic … [He] gave me a tremendous kick, “Taisez-vous, bête!” exclaimed he.’

Kelly unmasked and Jean-Georges discovered that he had kicked the management. ‘He made every possible apology’, but it is easy to see why it was his dancers, not their master, who went to court.

The choleric but distinguished ballet master died impoverished leaving an artistic reputation whilst being corporeally obliterated by urban development. None of his children followed his profession. Augustin founded a dynasty of well-regarded dancing masters. He was commemorated by them with a handsome memorial in St Stephen’s church, Norwich, which is still to be seen today.

[Previous Page :: Contents List :: Next Page]